A look at the life of Martin Luther King Jr.

In early April 1968, shock waves reverberated around the world with the news that U.S. civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee. A Baptist minister and founder of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), King had led the civil rights movement since the mid-1950s, using a combination of powerful words and non-violent tactics such as sit-ins, boycotts and protest marches (including the massive March on Washington in 1963) to fight segregation and achieve significant civil and voting rights advances for African Americans. His assassination led to an outpouring of anger among black Americans, as well as a period of national mourning that helped speed the way for an equal housing bill that would be the last significant legislative achievement of the civil rights era.

King Assassination: Background

In the last years of his life, King faced mounting criticism from young African-American activists who favored a more confrontational approach to seeking change. These young radicals stuck closer to the ideals of the black nationalist leader Malcolm X (himself assassinated in 1965), who had condemned King’s advocacy of non-violence as “criminal” in the face of the continuing repression suffered by African Americans. As a result of this opposition, King sought to widen his appeal beyond his own race, speaking out publicly against the Vietnam War and working to form a coalition of poor Americans–black and white alike–to address such issues as poverty and unemployment.

Did You Know?

Among the witnesses at the scene of King's assassination was one of his closest aides, Jesse Jackson. Ordained as a minister soon after King's death, Jackson went on to form Operation PUSH (People United to Save Humanity) and the National Rainbow Coalition and to run twice for U.S. president, in 1984 and 1988.

In the spring of 1968, while preparing for a planned march to Washington to lobby Congress on behalf of the poor, King and other SCLC members were called to Memphis, Tennessee to support a sanitation workers’ strike. On the night of April 3, King gave a speech at the Mason Temple Church in Memphis. In it he seemed to foreshadow his own untimely passing, or at least to strike a particularly reflective note, ending with these now-historic words: “I’ve seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land. And I’m happy tonight. I’m not worried about anything. I’m not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.”

Assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr.

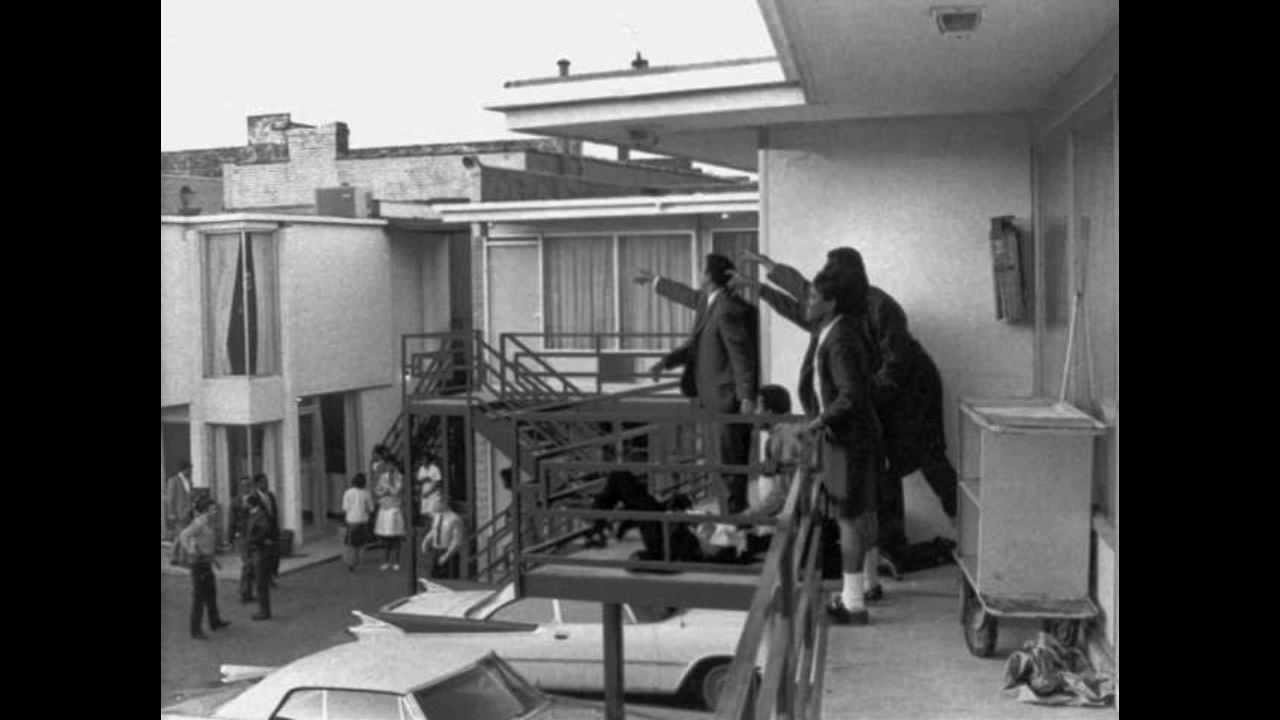

Just after 6 p.m. the following day, King was standing on the second-floor balcony of the Lorraine Motel, where he and associates were staying, when a sniper’s bullet struck him in the neck. He was rushed to a hospital, where he was pronounced dead about an hour later, at the age of 39.

Shock and distress over the news of King’s death sparked rioting in more than 100 cities around the country, including burning and looting. Amid a wave of national mourning, President Lyndon B. Johnson urged Americans to “reject the blind violence” that had killed King, whom he called the “apostle of nonviolence.” He also called on Congress to speedily pass the civil rights legislation then entering the House of Representatives for debate, calling it a fitting legacy to King and his life’s work. On April 11, Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1968, also known as the Fair Housing Act.

King Assassination: Seeking Justice

On June 8, authorities apprehended the suspect in King’s murder, a small-time criminal named James Earl Ray, at London’s Heathrow Airport. Witnesses had seen him running from a boarding house near the Lorraine Motel carrying a bundle; prosecutors said he fired the fatal bullet from a bathroom in that building. Authorities found Ray’s fingerprints on the rifle used to kill King, a scope and a pair of binoculars. On March 10, 1969, Ray pleaded guilty to King’s murder and was sentenced to 99 years in prison. No testimony was heard in his trial. Shortly afterwards, however, Ray recanted his confession, claiming he was the victim of a conspiracy. Ray later found sympathy in an unlikely place: Members of King’s family, including his son Dexter, who publicly met with Ray in 1977 and began arguing for a reopening of his case. Though the U.S. government conducted several investigations into the trial–each time confirming Ray’s guilt as the sole assassin–controversy still surrounds the assassination. At the time of Ray’s death in 1998, King’s widow Coretta Scott King (who in the weeks after her husband’s death had courageously continued the campaign to aid the striking Memphis sanitation workers and carried on his mission of social change through non-violent means) publicly lamented that “America will never have the benefit of Mr. Ray’s trial, which would have produced new revelations about the assassination…as well as establish the facts concerning Mr. Ray’s innocence.”

Impact of the King Assassination

Though blacks and whites alike mourned King’s passing, the killing in some ways served to widen the rift between black and white Americans, as many blacks saw King’s assassination as a rejection of their vigorous pursuit of equality through the nonviolent resistance he had championed. His murder, like the killing of Malcolm X in 1965, radicalized many moderate African-American activists, fueling the growth of the Black Power movement and the Black Panther Party in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

King has remained the most widely known African-American leader of his era, and the most public face of the civil rights movement, along with its most eloquent voice. A campaign to establish a national holiday in his honor began almost immediately after his death, and its proponents overcame significant opposition–critics pointed to FBI surveillance files suggesting King’s adultery and his influence by Communists–before President Ronald Reagan signed the King holiday bill into law in 1983. Construction is underway on a permanent memorial to King, to be located on the Mall in Washington, D.C., near the Lincoln Memorial–the site of King’s iconic “I Have a Dream” speech during the March on Washington in 1963.