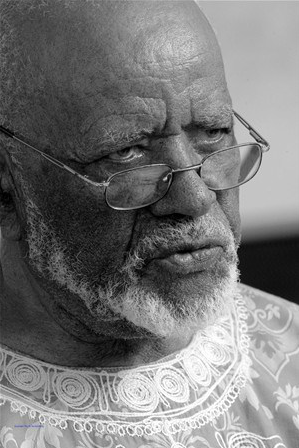

Celebrating The Legacy of Es’kia Mphahlele, The Father of Afrikan Humanism

Posted on 18 November 2013 by Thandisizwe Mgudlwa

Es’kia Mphahlele was a South African writer, educationist, artist and activist.

Prof. Mphahlele was born on the 17th of December 1919 in Pretoria, and he passed on, on the 27th October in 2008.

He was born Ezekiel Mphahlele but changed his name to Es’kia in 1977.

Mphahlele is celebrated as the Father of Afrikan Humanism.

His life’s work embraces his philosophy of Afrikan Humanism and offers over 50 years of profound insights on Afrikan Humanism, Social Consciousness, Education, Arts, Culture and Literature.

The critical thoughts expressed in his writing, reveal the foresight of someone who challenges us to: know our Afrika intimately, even while we tune into the world at large.

From the age of five he lived with his paternal grandmother in Maupaneng village, in Limpopo where he herded cattle and goats.

His mother, Eva, had taken him and his two siblings to go live with her in Marabastad (2nd Avenue) when he was 12 years old.

He married Rebecca Nnana Mochedibane (Mphahlele), whose family was victim of forced removals in Vrededorp, in 1945 (the same year his mother died).

Rebecca was a qualified Social Worker with a Diploma from Jan Hofmeyer School, in Johannesburg. Together with his wife, Mphahlele had five children.

When he left South Africa going into exile, he left behing his entire family, but his wife and kids.

He went for years without seeing them. He once tried taking advantage of a British passport before Nigeria’s independence. He applied for a visa through the consulate in Nairobi. He needed to get home to visit Bassie (Solomon), his younger brother, who was ill with throat cancer.

Sadly, his application was turned down.

And earlier, at the age of 15, he began attending school regularly and enrolled at St Peters Secondary School, in Rosettenville (Johannesburg).

The young Mphahlele finished high school by private study. That became his learning method until his PhD qualification.

He obtained a First Class Pass (Junior Certificate). He received his Joint Matriculation Board Certificate from the University of South Africa in 1943.

While teaching at Orlando High School, Mphahlele obtained his B.A. in 1949 from the University of South Africa, majoring in English, Psychology and African Administration.

In 1949, he received his Honours degree in English from the same institution.

While working at Drum magazine, Mphahlele made history by becoming the first person to graduate M.A. with distinction at UNISA. His thesis was titled : The Non-European Character in South African

English Fiction. He achieved this remarkable milestone in 1957.

English Fiction. He achieved this remarkable milestone in 1957.

From 1966-1968, under the sponsorship of the Farfield Foundation, Mphahlele became a Teaching Fellow in the Department of English at the University of Denver, in Colorado. This is when he read for and completed his PhD in Creative Writing.

In lieu of a thesis, he wrote a novel titled The Wanderers. He was subsequently awarded First Prize for the best African novel (1968-69) by the African Arts magazine at the University of California, in Los Angeles.

Mphahlele had obtained his Teacher’s Certificate at Adams College in 1940. He served at Ezenzeleni Blind Institute as a teacher and a shorthand-typist from 1941 to 1945. He and his wife moved their family to Orlando East, near the historic Orlando High School, in Soweto as he joined the school in 1945 as an English and Afrikaans teacher.

He protested against the introduction of Bantu Education (inferior education system which was meant for Black South Africans by the Apartheid regime), and as a result, his teaching career was cut short, and he was banned from teaching in South Africa by the Apartheid Government.

Mphahlele left South Africa and went into exile. His first stop was Nigeria.

He taught in a high school for 15 months and for the rest of the stay, at the University of Ibadan, in their extension programme.

Mphahlele also worked at the C.M.S. Grammar School, in Lagos.

He worked in the Department of Extra-Mural Studies at the University of Ibadan, travelling to various outlying districts to teach adults.

Each day, he taught a class from 5pm-7pm. While based in Paris, he became a visiting lecturer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

He also lectured in Sweden, France, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Sierra Leone, Ghana, Senegal and Nigeria.

Mphahlele spent twenty years in exile. He spent four years in Nigeria with his family. “It was a fruitful experience. The people of Nigeria were generous. The condition of being an outsider was not burdensome. I had time to write and engage in the arts” Mphahlele had said of his exile experience.

He was working with the best in Nigerian; playwright, poet and novelist Wole Sonyika; poets Gabriel Okara and Mabel Segun ;Amos Tutuola,a novelist; sculpture Ben Enwonnwu; and painters Demas Nwoko and Uche Okeke, and so on.

His visits to Ghana became frequent as each trip added more literary giants to his list of networks and colleagues.

The University of Ghana would invite him to conduct extramural writers’ workshops.

That is where he got to meet Kofi Anwoor (then George Awoonor Williams), playwright Efua Sutherland, poet Frank Kobina Parks, musicologist Professor Kwabena Nketia, historian Dr. Danquah, poet Adail-Mortty and sculptor Vincent Kofi.

Mphahlele attended the All African People’s Conference organised by Kwame Nkrumah in Accra, Ghana, in December 1958. “Ghana was the only African country that had been freed from the European colonialism that had swept over the continent in the 19th century. Most of the countries represented at Accra were still colonies,” remembered Mphahlele.

In Afrika My Music, Mphahlele recalled meeting with the late Patrick Duncan and Jordan Ngubane who were representing the South African liberal view. It was at this conference where he met Kenneth Kaunda, and listened to Franz Fanon deliver a fiery speech against colonialism.

Rebecca, his wife returned to South Africa towards the end of 1959, to give birth to their last born, Chabi.

They returned in February 1960. They were in Nigeria when they heard about the Sharpeville Massacre. “Yes, Nigeria and Ghana gave Afrika back to me. We had just celebrated Ghana’s independence,” Mphahlele had noted.

Mphahlele moved his family to France in August 1961, their second major move. And then he was appointed as the Director of the African Program of The Congress for Cultural Freedom and went to Paris.

They lived on Boulevard du Montparnasse, just off St. Michel, a few blocks from the Le Select and La Goupole restaurants.

Their apartment was soon to become a kind of crossroads for writers and artists: Ethiopian artist Skunder Borghossian; Wole Sonyika; Gambian poet Lenrie Peters; South African poet in exile Mazisi Kunene; Ghanaian poet and his beloved friend J.P. Clark; and Gerard Sekoto.

It was during his stay in France when Mphahlele was invited by Ulli Beier and other Nigerian writers to help form the Mbari Writers and Artists Club in Ibadan. They raised money from Merrill Foundation in New York to finance the Mbari Publications, a venture the club had undertaken.

Work by Wole Sonyika, Lenrie Peters and others were first published by Mbari Publishers before finding its way to commercial houses.

He edited and contributed to the Black Orpheus, the literary journal in Ibadan. He toured and worked in major African cities like Kampala, Brazzaville, Yaounde, Accra, Abidjan, Freetown and Dakar.

Mphahlele also attended seminars connected with work in Sweden, Denmark, Finland, West Germany, Italy, and the US.

He then went on to set up an Mbari Centre in Enugu, in Nigeria, under the directorship of John Enekwe. In 1962, at Makerere University, in Kampla, Uganda, they organised the first Africa Writers’ Conference.

The only South African who were able to attend were himself, Bob Leshoai who was on tour and Neville Rubin who was editing a journal of political comment in South Africa.

Two conferences, one in Dakar and another in Freetown were organised in 1963. Their aim was to throw into open the debate of the place of African literature in the university curriculum. They wanted to drum up support for the inclusion of African literature as a substantive area of study at university, where traditionally it was being pushed into extramural departments and institutes of African Studies.

Mphahlele had only planned to stay in Paris for two years, after which he would return to teaching.

Those experiences had made him yearn for the classroom again.

John Hunt, the Executive Director of the Congress for Cultural Freedom suggested that Mphahlele establish a centre like the Nigerian Mbari in Nairobi.

Mphahlele arrived in Nairobi in August 1963, and October had been set for Kenya’s independence.

By the time Rebecca and the children arrived, he had already bought a house.

Prior to that, he had been housed by Elimo Njau, a Tanzanian painter. Njau suggested a name everyone liked- Chemchemi, kiSwahili for “fountain”.

Within a few months, they had converted a warehouse into offices, a small auditorium for experimental theatre and intimate music performances, and an art gallery.

Njau ran the art gallery on voluntary basis. He mounted successful exhibitions of Ugandan artists Kyeyune and Msango, and of his own work.

“My soul was in the job. I was in charge of writing and theatre,” Mphahlele said on Africa My Music.

Their participants were from the townships and locations that were a colonial heritage.

Mphahlele would travel to outside districts to run writers’ workshops in schools that invited him, accompanied by the centre’s drama group.

Their traveling was well captured in Busara, edited by Ngugi wa Thiong’o and Zuka, edited by Kariara.

When the Alliance High School for Girls (just outside Nairobi) asked him to write a play for its annual drama festival, in the pace of the routine Shakespeare, Mphahlele adapted one of Grace Ogot’s The Rain Came – a short story, and called it Oganda’s Journey. “The most enchanting element in the play was the use of traditional musical idioms from a variety of ethnic groups on Kenya. A most refreshing performance, which exploited the girl’s natural and untutored acting,” remarked Mphahlele.

After serving for two years, he felt he had done what he had come for, as he had indicated before taking the job that he would not stay for more than two years.

He turned down a lecturing post at the University College of Nairobi as they could only offer him a one year contract which he could not take.

Mphahlele moved his family to Colorado in May 1966.

Here, they rented a house, fixed schooling for the children and prepared for the plunge.

Mphahlele was joining the University of Denver’s English Department.

He was granted a tuition waver by the university for the course work he had to do before he could be admitted for the PhD dissertation.

Notably, he paid for the Afrikan Literature and Freshman Composition himself.

It was during his primary school days (as he recalls in his second autobiography Africa My Music) when he started rooting everywhere for newsprint to read.

He recalled always looking for any old scrap of paper to read. He further recalled a small one-room tin shack the then municipality called a reading room, on the western edge of Marbastad.

Prof. Mphahlele remembered it being stacked with dilapidated books and journals, junked by some bored ladies in the suburbs.

He dug out of the pile Cervantes’s Don Quixote, and went through the whole lot like a termite, elated by the sense of discovery, recognition of the printed word and by the mere practice of the skill of reading. Cervantes stood out in his mind, forever.

Another teacher that fired his imagination was the silent movies of the 1930s.

He enjoyed a combination of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza together with Laurel and Hardy, with Buster Keaton.

Mphahlele would read the subtitles aloud to his friends who could not read as fast or at all, amid the yells and foot stamping and bouncing on chairs to the rhythm of the action.

While still based in Paris in the early 1960s, he published his second collection of short stories, The Living and Dead and Other Stories.

In 1962, the year he called “The Year of My African Tour”, he published The African Image, in Nigeria, Bulgarian, Swedish, Czech, Hebrew and Japanese, and Portuguese were to follow.

His first autobiography, Down Second Avenue was doing so well such that it was translated to French, German, Serbo-Croa.

And in 1964, he published The African Image. In December of 1978, South African Minister of Justice took Mphahlele’s name off the list of writers who may not be quoted, and whose works may not be circulated in the country.

Only ‘’Down Second Avenue’’, ‘’Voices in the Whirlwind’’ and ‘’Modern African Stories’’ which he had co-edited could then be read in the country.

Other publications remained banned.

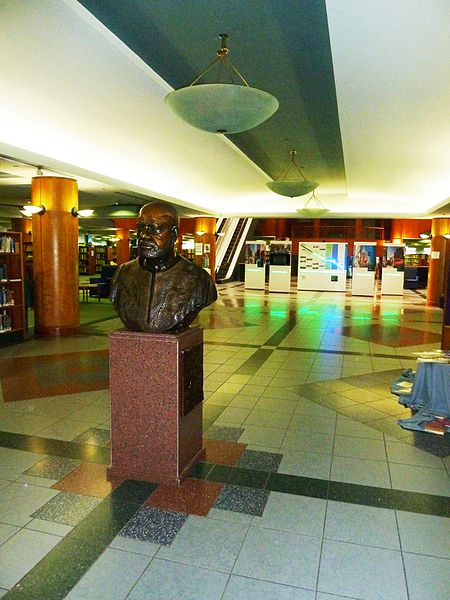

The first comprehensive collection of his critical writing was published under the title ES’KIA, in 2002, the same year that the Es’kia Institute was founded.

Es’kia Mphahlele’s life and work is currently found in the efforts of The Es’kia Institute, a non-governmental, non-profit organisation based in Johannesburg.

Mphahlele had set foot on South African soil again on the 3rd of July, 1976, at the Jan Smuts Airport (now called the O.R.Tambo International Airport).

He had been invited by the Black Studies Institute in Johannesburg to read a paper at its inaugural conference.

“I was emerging on to the concourse when I was startled by a tremendous shout. And they were on top of me – some one hundred Africans, screaming and jostling to embrace me, kiss me. Relatives, friends and pressmen from my two home cities – Johannesburg and Pretoria. I was bounced hither and thither and would most probably not have noticed if an arm or leg were torn off of me, or my neck was being wrung. Such an overwhelming ecstasy of that reunion. The police had to come and disperse the crowd as it had now taken over the concourse,” Mphahlele remembered.

Prof. Mphahlele officially returned to South Africa in 1977, on Rebecca’s birthday (August 17).

“When I came back, things were much worse. People were resisting what had become a more and more oppressive government. We came back at a dangerous time. It was a time when we knew we would not be alone, and that we would be among our people,” Mphahlele said in 2002.

He waited for six months for the University of the North to inform him whether he would get the post of English professor which was still vacant. The answer was ‘no’.

The government service of Lebowa offered him a job as an inspector of schools for English teaching. While, Rebecca had found a job as a social worker.

In his autobiography Afrika My Music, he describes how the ten months of being an inspector was like.

“I had the opportunity of travelling the length and breadth of the territory visiting schools and demonstrating aspects of English teaching. I saw for myself the damage of Bantu Education had wrought in our schooling system over the last twenty-five years. Some teachers could not even express themselves fluently or correctly in front of a class, and others spelled words wrongly on the blackboard”.

Then in 1979, he joined the University of the Witwatersrand as a Senior Research Fellow at the African Studies Institute.

He founded the Council for Black Education and Research, an independent project for alternative education involving young adults.

In 1983, he established the African Literature Division within the Department of Comparative Literature, at the University of the Witwatersrand, where he became the institution’s first black professor.

He was permitted to honour an invitation from the then Institute for Study of English in Africa at Rhodes University. This was a two months research fellowship where his proposal of finishing his memoir Afrika My Music, which he had began in Philadelphia was accepted.

After his retirement from Wits University in 1987, Mphahlele was appointed as the Executive Chairman of the Board of Directors at Funda Centre for Community Education.

He has been the recipient of other numerous international awards that have sought to pay tribute to the efforts of his tireless scholarly work.

In 1969, he was nominated for the Nobel Prize for Literature, and in 1984, he was awarded the Order of the Palm by the French Government for his contribution to French Language and Culture.

Prof. Mphahlele was the recipient of the 1998 World Economic Forum’s Crystal Award for Outstanding Service to the Arts and Education, and a year later he was awarded the Order of the Southern Cross by former President Nelson Mandela.

Photo Credit: Wikipedia.org