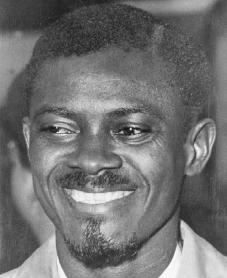

Haile Selassie I

Emperor (1892–1975)

Emperor

Haile Selassie I, worked to modernize Ethiopia for several decades

before famine and political opposition forced him from office in 1974.

Synopsis

Born in Ethiopia in 1892, Haile Selassie was crowned emperor in 1930 but exiled during World War II after leading the resistance to the Italian invasion. He was reinstated in 1941 and sought to modernize the country over the next few decades through social, economic and educational reforms. He ruled until 1974, when famine, unemployment and political opposition forced him from office.Early Years

Haile Selassie I was Ethiopia's 225th and last emperor, serving from 1930 until his overthrow by the Marxist dictator Mengistu Haile Mariam in 1974. The longtime ruler traced his line back to Menelik I, who was credited with being the child of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba.He was born in a mud hut in Ejersa Gora on July 23, 1892. Originally named Lij Tafari Makonnen, he was the only surviving and legitimate son of Ras Makonnen, the governor of Harar.

Among his father's important allies was his cousin, Emperor Menelik II, who did not have a male heir to succeed him. Tafari seemed like a possible candidate when, following his father's death in 1906, he was taken under the wing of Menelik.

In 1913, however, after the passing of Menelik II, it was the emperor's grandson, Lij Yasu, not Tafari, who was appointed as emperor. But Yasu, who maintained a close association with Islam, never gained favor with Ethiopia's majority Christian population. As a result Tafari became the face of the opposition, and in 1916 he took power from Lij Yasu and imprisoned him for life. The following year Menelik II's daughter, Zauditu, became empress, and Tafari was named regent and heir apparent to the throne.

For a country trying to gain its foothold in the young century and curry favor with the West, the progressive Tafari came to symbolize the hopes and dreams of Ethiopia's younger population. In 1923 he led Ethiopia into the League of Nations. The following year, he traveled to Europe, becoming the first Ethiopian ruler to go abroad.

His power only grew. In 1928 he appointed himself king, and two years later, after the death of Zauditu, he was made emperor and assumed the name Haile Selassie ("Might of the Trinity").

Strong Leader

Over the next four decades, Haile Selassie presided over a country and government that was an expression of his personal authority. His reforms greatly strengthened schools and the police, and he instituted a new constitution and centralized his own power.In 1936 he was forced into exile after Italy invaded Ethiopia. Haile Selassie became the face of the resistance as he went before the League of Nations in Geneva for assistance, and eventually secured the help of the British in reclaiming his country and reinstituting his powers as emperor in 1941.

Haile Selassie again moved to try to modernize his country. In the face of a wave of anti-colonialism sweeping across Africa, he granted a new constitution in 1955, one that outlined equal rights for his citizens under the law, but conversely did nothing to diminish Haile Selassie's own powers.

Final Years

By the early 1970s famine, ever-worsening unemployment and increasing frustration with the government's inability to respond to the country's problems began to undermine Haile Selassie's rule.In February 1974 mutinies broke out in the army over low pay, while a secessionist guerrilla war in Eritrea furthered his problems. Haile Selassie was eventually ousted from power in a coup and kept under house arrest in his palace until his death in 1975.

Reports initially circulated claiming that he had died of natural causes, but later evidence revealed that he had probably been strangled to death on the orders of the new government.

In 1992 Haile Selassie's remains were discovered, buried under a toilet in the Imperial Palace. In November 2000 the late emperor received a proper burial when his body was laid to rest in Addis Ababa's Trinity Cathedral.

SOURCE: Biography.com